by Dr Harley Pope

Last week, I delivered a series of workshops to 1st and 2nd year students on food systems thinking and literacy at the FoodBioSystems Doctoral Training Programme (DTP) summer school. While I focused on developing their capacity to think systemically, I thought it interesting to reflect on why students are being encouraged to situate their work within the food system.

When I was doing my doctoral research, my supervisors helped me reflect on the nature of the contribution I was making to our collective knowledge. Yes, I was potentially enhancing our shared understanding. It was a beneficial thing to do for myself and others, but the contribution itself was incremental and miniscule when compared to the whole body of knowledge.

Through increasing specialism, the constraints of doctoral research, and the reductive aspects of the scientific method, students can find themselves working on some small, hyper-focused element of a much larger situation. And that can be ok – good even, as there is a well-defined need for targeted high-resolution knowledge. So why might they benefit from grappling with the bigger picture? Let’s take the food domain as an example.

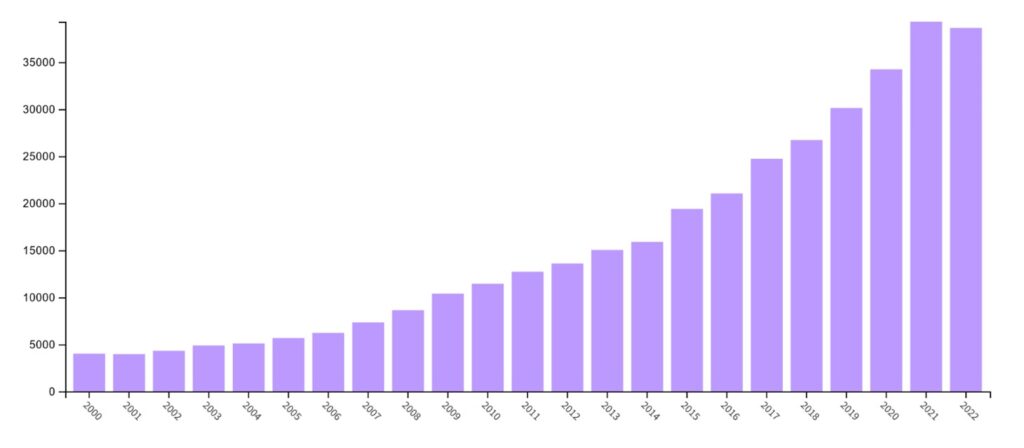

Bar chart illustrating the annually increasing number of publications that use the term “food system”

Source: Web of Knowledge. Search term “food system”.

Firstly, an increasing number of academics are framing their work in terms of how it relates to the concept of “food systems.” From less than 5000 unique mentions in journal articles in 2000, as of 2022, there are now well over 35,000 articles published annually that reference food systems. If students want to be a part of this conversation, or collaborate with others, they need to effectively situate their work within a wider context or system.

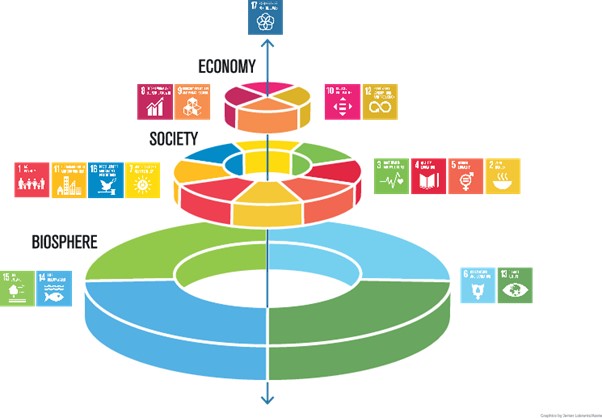

The food system is also frequently mentioned and discussed at length in food policy too. In the UK, the National Food Strategy (2021) devotes its entire second chapter to the need for systems thinking in designing and implementing effective food policy. At the UN Level, “Zero Hunger” is the second Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) – but as the Stockholm Resilience Centre has illustrated, they can all be seen as related to food in some way. Effective action towards one goal, often means addressing other goals at the same time.

The SDG Wedding Cake – how they are all related to food

Source: Azote for Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University CC BY_ND 3.0

Why are food systems cropping up with increasing regularity within the academic literature? The use of the term correlates with our growing understanding of the complex, interdependent nature of the challenges that we now face due to the current and predicted future impacts of human activities on the planet. Although these impacts, such as climate change and biodiversity loss, are already driving changes within the food system that threaten its functioning, people are waking up to the fact that there are not necessarily quick and easy solutions. Both the challenges and potential opportunities for addressing them involve different parts of the food system, so if we want to do something about them, we can’t begin to do so if we don’t work across disciplines, sectors, institutions, and geo-political boundaries.

Collaboration in this endeavour is critical, but it also must be fair. We need to understand the trade-offs and costs to changing behaviours and processes so that the burden does not fall on the shoulders of specific stakeholders, but instead is more fairly distributed across the system. For that to happen requires their meaningful representation. We also need to consider and evaluate different policy and technology options in terms of whether they will generate their intended impacts, and how these proposed solutions might need to change in the light of changing system dynamics and behaviour over time. If we are working on some technical aspect of the food system and have not considered its potential impact, it may reinforce or amplify system behaviours that do not work towards higher order goals.

For doctoral students, reflecting on the broader context of their work with respect to the food system has immediate as well as long term benefits. In the short term, it can help them in the research process in three main ways:

- Problem definition – it can help students develop and refine the context and rationale for their thesis – handy for research question formulation and writing the introduction. In some cases, it may inspire a change in direction and reorientation towards a more stimulating and resonating topics

- Insight generation – it can help students to develop their research design and methodology choice providing a more insightful analysis.

- Outcomes and impacts – It can help students in writing up their conclusions and reflecting on the degree to which they can be generalised. Importantly, it can help with the next steps – helping them to contextualise and communicate their work to different audiences and justify the importance of their research when looking for further funding.

The benefits of learning food systems thinking are not limited to the process of designing, implementing, and writing up research. Systems thinking requires the refinement of critical, analytical, and interpersonal skills the benefits of which stretch far beyond the limits of the doctoral process.