Written by PhD student Megan Sherlock from SCENARIO DTP

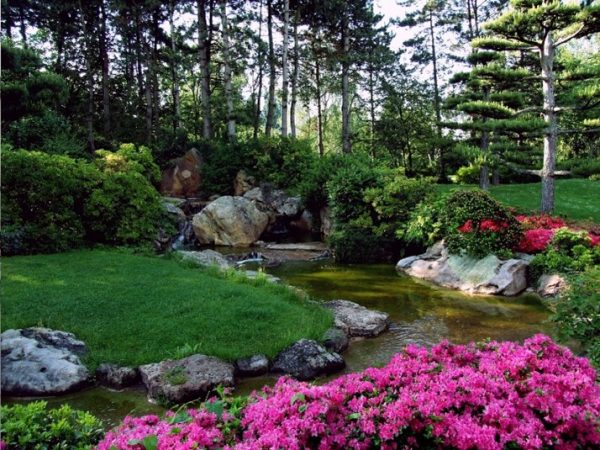

Attendees at COP28’s “Traditional Knowledge: Ancestral Gardens” demonstrate just how varied traditional gardens can be, from English rolling lawns to Japanese zen gardens.

A lively discussion at this week’s traditional knowledge and gardens workshop has shown that what you think of when you hear the word “garden” can depend on your cultural background. Many attendees described what made up their countries’ traditional gardens, as well as features that can be found in common. But what do some of these traditional gardens look like?

A scene you may be familiar with is a traditional English garden. Characterised by rolling lawns, and diverse native planting, English gardens often blend into their surroundings to avoid disturbing the nature around them. These gardens present an idealised view of nature, often resembling picturesque and romanticised landscape paintings. Even smaller, urban gardens mimic this design with lawns of grass and colourful flower beds.

Mediterranean gardens, on the other hand, such as those found in Greece and Turkey, are traditionally made up of drought-tolerant plants found in terracotta pots to limit water loss. White-washed walls reflect sunlight away from the garden, whilst stone pathways connect separate areas.

Traditional Japanese gardens are a microcosm of the natural world, with water features such as ponds representing lakes and large stones, mountains. Paths and pavilions allow for access to the water, with additional smaller gardens such as zen (raked gravel or sand to represent water) found inside. Plant species are native and seasonal, requiring little management from garden owners to better represent the wild aspect of nature.

Moroccan gardens, also known as ‘riads’, are courtyards found in the centre of houses, made up of stonework and intricate tiling. Central water features such as fountains provide cooling and relaxation, whilst colourful drought-tolerant shrubs and small trees are placed in plant pots or pits.

Traditional Chinese gardens contain three main elements: water to represent life, stone to represent death and plants to provide different meanings. Pine, for example, is the symbol of longevity. Bridges and viewing pavilions allow for a closer look into water features, and separate the garden into ‘scenes’, reminiscent of a collection of landscape paintings. Moon Gates (such as those seen here) offer an entryway to the often-enclosed gardens, providing an escape from the outside world.

Many of the differences seen within these traditional gardens are due to the climate, history, and religion of the countries they are found in. Plant choices within gardens are a direct result of the climatic conditions the garden experiences. For example, in Greek gardens, drought-tolerant species are planted in terracotta pots to ensure that the plants can survive in hotter temperatures, whilst Moroccan gardens often contain a central water feature to help cool the air.

The history of the country itself also influences features found within their traditional gardens. American gardens are often a mixture of English, Spanish and Dutch features due to their past colonisation of America, removing existing Native American gardens which are built for sustenance and spirituality. German gardens also focus on growing food, due to their creation after WWII when poverty and malnourishment was common. Traditional garden design can further reflect the religion and spirituality of the surrounding culture. The focus of Japanese gardens, mimicking the natural world and inspiring harmony and meditation, stems from Buddhist and Shintoist beliefs.

Regardless of what a “traditional garden” looks like, it can be used as a tool for conservation. Using native plants can help support local biodiversity of plants and animals. This is particularly true for pollinators, whose importance was stressed at the “Bee the change” event, a global campaign introduced at COP28. The United Nations University in Japan has shown that gardens can form a niche habitat where certain species of otherwise extinct snails, lizards, and fish can exist. Gardens also provide easy access to nature, particularly in urban areas where greenspace may be lacking, inspiring more people to protect and appreciate wildlife.

Whilst gardens can be useful in combating biodiversity loss and climate change, they themselves are not immune from these effects. As temperatures rise and rainfall becomes more sporadic, traditional gardens in colder, wetter regions, such as England, will no longer be fit for purpose. We will have to alter our traditional garden designs to reflect climatic changes, meaning that they will no longer reflect the culture of their country, but instead the need to adapt to survive.